Captain Larry Lowe Taylor was graduated from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, in June 1966 and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in armor. After completion of the armor officers basic course, he concluded that being on the ground was not in his future. He attended flight training and was later assigned to one of the Army’s first Cobra companies in Vietnam.

With the 1st Squadron, 4th U.S. Cavalry, 1st Infantry Division, Taylor flew well over 2,000 combat missions in the UH-1 and Cobra helicopters. He was engaged by enemy fire 340 times and was forced down five times. He was awarded 61 combat decorations, including 44 Air Medals, the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry, two Bronze Stars, and four Distinguished Flying Crosses. There were many harrowing operations, but one in particular rises above the others. On June 18, 1968, Taylor rescued a four-man long range reconnaissance patrol at significant risk to his life. For his heroic actions that night, he was awarded the Silver Star. That award has been recommended for an upgrade to the Medal of Honor. Captain Taylor concluded this military service with the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment in West Germany.

After leaving the Army, Taylor operated a roofing and sheet metal company in Chattanooga. He has been involved in several veterans’ organizations.

Taylor and his wife, Toni, reside in Signal Mountain, TN.

From the Chattanooga Times Free Press, July 10, 2023:

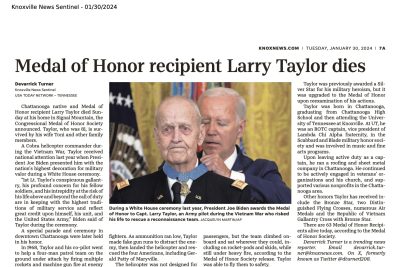

Officially, Signal Mountain’s Larry Taylor will receive the Medal of Honor for his helicopter rescue of four fellow soldiers in Vietnam in June 1968.

Taylor, then a first lieutenant in the U.S. Army, sees it differently.

“I just got caught doing my job,” he said in a Monday telephone interview. “I didn’t plan on it. Didn’t expect it. It just happened.”

Taylor said President Joe Biden called last weekend to tell him he would receive the nation’s highest military award. Taylor said he was told the ceremony will be conducted “in the next 30 days” or so in Washington.

The president “told me to wear whatever I’d wear to Sunday school,” Taylor said. “We talked for quite a few minutes.”

Taylor’s recognition comes 55 years after he flew a Cobra helicopter to a village near Saigon, where he plucked up four soldiers on a reconnaissance mission who’d been surrounded by about 80 North Vietnamese troops. One of the soldiers Taylor rescued was David Hill, who for years has championed efforts to get his buddy a Medal of Honor.

“Larry Taylor is a true American hero,” Hill said in a 2022 email. “He literally saved my life.”

Chattanooga veteran Carl Poston said he’s spent years making Taylor’s Medal of Honor case alongside Hill, fellow veterans Ray Adkins and Mike Holden, and retired four-star Gen. B.B. Bell. He summed up in a single word the team’s reaction to Taylor’s honor.

“Finally,” Poston said in a Monday telephone interview. “We’ve been at this for seven years.

“It’s been long and arduous, but it was Gen. Bell who kind of pushed it over the top. When a four-star general wants to come on board, you’re thankful,” said Poston, who spent 28 years in the Army on active duty and in the reserves.

·

https://patriotpost.us/alexander/84113-larry-taylor-medal-of-honor-award-pending-dot-dot-dot-2021-11-10:

Larry Taylor grew up in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and he seemed destined for military service: “I’d always known I’d join the military. My granddaddy fought in the Civil War, my great uncle in WWI, and my dad and uncles in WWII. I didn’t have to be drafted to fight in Vietnam. It was the honor of my life.”

His path into the Army during Vietnam was through ROTC at the University of Tennessee. Graduating in June of 1966, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant. He then graduated from the Armor Officers Basic Training course at Fort Knox, Kentucky, but went on to the Army Flight School at Fort Walters, Texas.

According to Larry: “I was in Armor branch [and] they said, ‘Well, what do you think about this tank?’ I said, ‘It sucks. I want to go to flight school.’”

Larry says: “My heart yearned for the clouds. I had my fixed-wing pilot’s license, and I figured a helicopter couldn’t be too difficult. There’s not much to say about helicopter school, other than it was harder than I thought. Knowing how to fly a fixed wing hadn’t helped much — if anything, the old habits made learning the helicopter a little harder — but as soon as I found the hover button, boy did my life change. I couldn’t wait to get to Vietnam. Lord forgive my innocence.”

Upon graduation, Larry joined one of the earliest Army Cobra helicopter companies in Vietnam: “There were nine brand new Cobra attack helicopters waiting for us when I arrived at 1-4 CAV in Bien Hoa. We ran those things into the ground, supporting 1st Infantry Division’s Long-Range Reconnaissance Patrols. Those boys wouldn’t be out 15 minutes before the Viet Cong surrounded them. The electromagnetic indicators we had in the Cobras showed us the direction of the LRRP team, and as fast as that aircraft flew, it didn’t take long to reach them; the indicators didn’t show us how to get back to base, which led to a lot of funny stories … and too many horrible ones for the Huey pilots. Not everyone who got lost made it back.”

Larry says of those flight operations that he was “scared most of the time, but that’s what we did.” He adds: “I don’t know if it was some spiritual connection or the fact that we shared a bond of brotherhood I’ve never seen anywhere else, but whenever I came in rocking my minigun … I swear I could feel the LRRP team’s relief. I was their savior. But to the enemy, I was the angel of death, come to collect their souls.”

Of all the missions he flew, one of those Larry survived in order to ensure the members of an LRRP would also survive is epic among Army Cavalry combat helicopter pilots. It is taught in Ranger school to this day.

On one June night in 1968, he was called to action: “The call that changed my life came at around 2100. Higher up had sent four LRRP teams to reconnoiter a small village. I’d known it was a doomed mission from the start, and told my CO as much, but sometimes the higher echelons of combat did not listen to the guys pulling the triggers. Chatter over the net crackled and screeched but the words came as clear as the desperation in the voice — ‘We’re surrounded!’”

It was Sgt. Dave Hill who radioed that he and his Wild Cat 2 LRRP team — Team Leader PFC Robert P. Elsner, Sgt. Billy Cohn, and Specialist 4 Gerald Paddy, another Tennessean — were trapped. “We settled in and called for support,” Hill recounts, and Taylor, call sign “Darkhorse Three Two,” answered the call. (Larry says that “sometimes Dave’s rank varied depending on which CO he had offended that week.”)

Larry: “My heart pounded and I had to clench my fists to keep them from shaking. I’d flown over 2,000 missions, saved LRRP teams on hundreds of different occasions, but this time felt different. My copilot had drawn silent and focused after hearing the call, and he carried the same urgency that resonated in every booted step. I cursed the number of buttons and switches as I moved through the same sequence I’d done countless times before to get my Cobra started. Lights flickered to life with an electric hum as beeps and buzzes sounded through the helmet. The turbine engine whirred and the blades swatted the air. Lights, gauges, everything in check. Radio call, roger, all clear for take-off. ‘Hold on,’ I warned my copilot as I increased the throttle. The turbines screamed to life and I pulled on the collective. My stomach fell to my feet as we climbed into the sky.”

Less than half-an-hour into the mission, he says: “We found the LRRP team in the middle of a rice paddy larger than a football stadium, surrounded by a reinforced company of North Vietnamese. We flew around that rice paddy for what seemed like an eternity providing cover while the LRRP team repositioned for extraction. I heard the plink of enemy bullets as they found their mark on my Cobra and returned in kind. No one shot at me twice. No one ever shot at a Cobra twice. Miniguns ripped the air with a stream of lead and rockets smashed the ground with explosive death, but the enemy refused to surrender with their prey so close.”

It soon became clear to Taylor and his weapons officer Bill Ratliff the extent of the danger the LRRP faced. “They were gonna die,” says Taylor. “There were four of them and they were surrounded by about 60 [enemy combatants] in a ring.”

Larry: “I called in illumination rounds that cast a portentous glow over the battleground, then asked when the hell the extraction would get there. ‘Stand by’ they’d told me. ‘I need those damn Hueys,’ I told them, wishing my ammo gauge had another zero after the 110. I don’t care how many helos are down, get that extract here now! More bullets plinked against the hull. A few more squeezes on the trigger and I’d be a flying chunk of metal.”

From the ground: “We’re pinned down, get us out! God, we’re going to die out here.”

“Not on my watch!” I said, drawing enemy fire even as I exposed their positions. There were still too many. I radioed higher but they were about as helpful as tits on a boar. ‘I’m going to extract them myself.’ The response was ‘negative-negative-negative, you will belay that.’ They’re going to die. ‘Standby … Standby … Standby …’“

Hill, the only member of the Wild Cat 2 team still living today, described the actions of Taylor and his WO Ratliff: “Over the next 35 minutes, they continually made rocket and gun runs around us.”

Under heavy fire, Larry says, “We began to run out of rockets and run out of ammunition and you couldn’t see anything.”

When the two Cobras were dry, having spent the last of their 152 rockets and almost all of their 16,000 rounds of 7.62-mm minigun ammo, and low on fuel, Larry radioed his flight team leader and requested to “Run out to 100 yards and lay down.” By all accounts, survival prospects after making that landing were slim to none, but there were no transport helicopters in the area capable of making the extraction, and time was up.

Taylor to headquarters: “What the hell are you waiting for? Either get me a Huey, or I’m extracting them.”

Permission denied: “The area is too hot, the team needs to move two clicks southwest.”

Taylor: “What part of ‘they’re surrounded’ don’t you understand? Forget it. I’m getting my men out. … I am exercising my prerogative as the senior commander on the scene!” Next, “I switched the radio channel back to the LRRP team. ‘You guys still have your claymores?’” The answer was “Roger” so I let them know, “I only got enough rounds for a quick pass. Set up them claymores, aim them toward the village, blow them after I make my pass, then sit tight. I’ll come find you.”

Larry: “One hundred and ten rounds from a minigun sounds like a small burp, but the explosion from a few claymores will rock the dust off a shelf from a hundred yards away.”

Hill says in the deadly darkness of that night, “All of a sudden we feel this down draft of wind, and here comes Taylor’s Cobra and he’s landing.”

The LRRP team was out of ammo as they ran for Taylor’s bird, but Dave Hill had a bag of grenades. He intentionally fell back behind the other three, providing cover by stopping every ten yards and throwing grenades toward the enemy lines. He was also awarded a Silver Star for his actions that night.

Of course, a Cobra gunship has no internal troop transport capability. So the LRRP team jumped on the helicopter skids and rocket pods and held on for life. Taylor says: “Two of them jumped on the far side. They were sitting on the skid holding on to the strut and the other two jumped on the rocket pods.” Hill was one who straddled a rocket pod and “rode it like a horse backwards” out of harm’s way.

Ratliff advised Taylor that their low fuel warning lights had come on before setting down in that rice paddy. As they lifted off, he said they had less than 20 minutes. But the flight time to get the LRRP out of harm’s way and then make the short hop to their base would take at least 25 minutes. Larry declared, “So we are going to make a 25-minute flight on 20 minutes of fuel.” No problem.

Of his actions, Larry simply observed: “I just got caught doing my job. I didn’t plan on it. Didn’t expect it. It just happened. That’s what you do. I told my men, ‘You never leave a man on the ground,’ and we never did, and I never lost a man. Not one. … I’d flown thousands of missions in Vietnam and saved countless lives. But none had meant so much to me as the four we saved that night, for life had never become so sweet as the night I became the angel of death … no man left behind.”

As described in the 1st Infantry Division account of his flight out: “Moving carefully but steadily upward and away from the area, still taking hits from VC small arms fire, Taylor was finally able to level off at 2,000 feet (out of small arms range) and turn southwest toward Saigon. After about 15 minutes of ‘white-knuckle’ piloting, the ‘Cobra-turned-troop-transport,’ with all four LRRPs still aboard, landed gingerly within the fenced confines of the Saigon Waterworks, near Tan Son Nhut Air Base. The team quickly jumped off, motioning their thanks to the Cobra crew via ‘thumbs-up’ and salutes, as Taylor lifted off for his Phu Loi base.”

Over the last five years, LRRP team members Dave Hill and others initiated a Department of Defense petition to review and upgrade Larry’s Silver Star to a Medal of Honor. According to Hill: “Larry Taylor is a true American hero. He literally saved my life. One of the gaps in my life is Larry never got his due, so, that’s our crusade in our lives at this point.”

But the advocacy for Larry’s DD149 Request for Reconsideration review and upgrade of his Silver Star to a Medal of Honor languished until being revitalized by my friend, Gen. B.B. Bell (USA-Ret.), advisory board chairman of the National Medal of Honor Heritage Center. That review is now at the Pentagon and underway and can take more than a year. Larry is battling cancer, and it is our hope that a determination on this award will come soon.

Notably, according to 1-4 CAV folklore, at some point in the communication exchange that night after being denied his request to rescue the team, “one of the pilots” accused, over an open mic, the officer in the chain of command above him of “having unnatural relations with his mother.” But the original refusal to recommend Taylor for a Medal of Honor has less to do with that insult than his direct defiance of orders. However, it is notable that many Medals of Honor have been awarded to those defying order – and that makes sense given those orders related to just how deadly the situation was.

Larry Taylor, thank you, and we will not rest until the recognition you have earned has been confirmed.

Footnote: I should mention that when Larry returned to the U.S. in 1973 after his final combat tour, he and other veterans changed into civilian clothing before leaving the plane in San Fransisco in order not to be targeted by anti-war protestors. Unfortunately for one protestor in the airport terminal confronted Larry, ultimately spitting on his shoes, and predictably that did not end well. No word on how well that protestors broken jaw healed, but it was a fitting response.

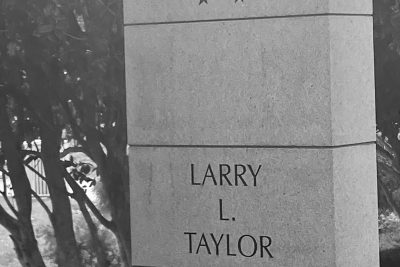

- Rank: Captain

- Date of birth: 13 May 1941

- Date of death: 28 January 2024

- County: Hamilton

- Hometown: Signal Mountain

- Service Branch: Army

- Division/Assignment: 1st Squadron, 4th U.S. Cavalry, 1st Infantry Division

- Conflict: Vietnam

- Awards: Medal of Honor, Silver Star, two Bronze Stars, four Distinguished Flying Crosses, Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry

- Contact us to sponsor Larry L. Taylor

Image Gallery

Click a thumbnail below to view at full size.