John Douglas Ward Jr

Private First Class

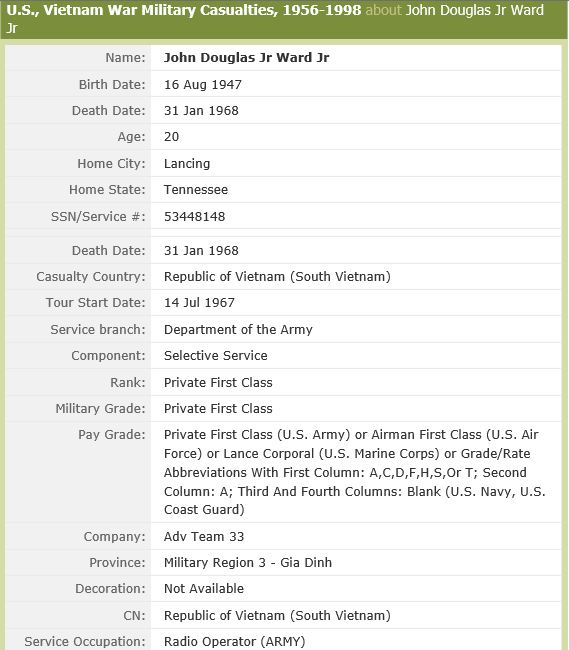

Personal Data:

Home of Record Lancing, TN

Date of birth 16 August 1947

Military Data

Service Army of the United States

Grade at loss E3

Rank Private First Class

ID No 53448148

MOS 05B20 Radio Operator

Length Service 01

Unit Advisory Team 33, HQ, MACV ADVISORS, MACV

Casualty Data:

Start Tour 0714 14 July 1967

Incident Date 31 January 1968

Casualty Date 31 January 1968

Age at Loss 20

Location Gia Dinh Province, South Vietnam

Remains Body recovered

Casualty Type Hostile, died outright

Casualty Reason Ground casualty

Casualty Detail Gun or small arms fire

Vietnam Wall Panel 36E Line 041

PFC Advisory Team 33 Vietnam PH – Tennessee

Burial: Mount Hope Cemetery, Morgan County, Tennessee, USA

James Brooks

jim.brooks@us.army.mil

Senior Commander

3518 Calvelli Court

San Jose, CA 95124 USA

I will always remember.

On the first full day of the Vietnam Tet offense in Ban Me Thuot, Darlac Province, advancing infantry of the 32d NVA Regiment attacked the 2d Battlion of the 45th ARVN Infantry Regiment, 23 ARVN Infantry Division. The close-range battle raged all day within the city. The 2d ARVN Battalion was successful in repelling the attacking 32d NVA Regiment. The MACV advisor team was on the front lines. John Ward, radio operator was killed by AK-47 fire at close range. He did not suffer. Major Joe Weis, US Army, was killed at the same time near John. John’s immediate commander, Captain David Gannon, was wounded. I have more details, but I am out of space.

–Jim Brooks, February 09, 2003

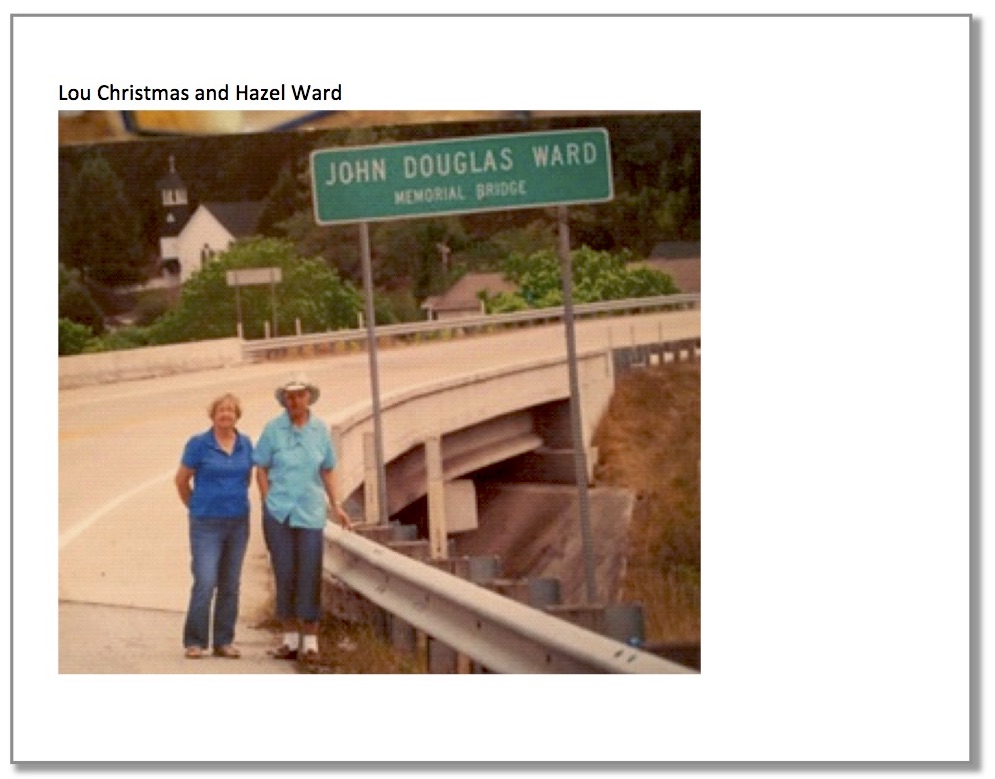

A Sign In Lancing, by Michael W. Nance

I remember several years ago when the overpass bridge in Lancing was constructed. The long awaited bridge’s purpose was to span the busy railroad and eliminate the long wait time often encountered when driving through Lancing. I still remember the first time I saw the sign memorializing the overpass bridge to John Douglass Ward. I asked my father and mother about Doug, and they both shared with me a few brief stories about growing up in Lancing with him. The story I remember most is that of his tragic death during the Vietnam War. I know my Uncle Gene Nance, who is also a Vietnam Veteran, never crosses that bridge without remembering his old friend Doug. Last week as I was traveling over the overpass bridge I made a commitment to myself to research Doug’s military service and write a story regarding his sacrifice to our great country. After researching Doug’s story I came to realize that the sign placed as a memorial to Doug’s service told not only his story, but the story of an entire generation of Veterans who deserve to be recognized for their sacrifice.

John Douglas Ward Jr. was born on August 16, 1947 to his proud parents, John and Hazel Ward longtime residents of Lancing, Tennessee. He was the only son of John and Hazel and is remembered by several local residents of the small town even today. Doug, as he was called, was a known prankster and enjoyed every moment of life. Some people still remember Doug driving his car with a stuffed bear in the front passenger seat of his convertible Ford Mustang. My Uncle also shared a story of their youth, where he and Doug placed a spinner type hub cap on the edge of the road in Lancing, near where the house of Allen Nance resides today. They would tie fishing line to the hub cap and run the line underneath the road through a culvert. When a passerby would see the hub cap it would naturally draw their attention and they would stop and attempt to retrieve it. About the time the unlucky victim of this prank would reach for the hub cap, he and Doug would quickly pulled it through the culvert. They had several laughs in the perpetration of this prank, although at least on one occasion a local resident became angry and chased them through the woods. Doug went on and graduated Central High in 1965 and later worked at Caterpillar in Joliet, Illinois. In September of 1966 Doug was inducted into the United States Army. He underwent basic training at Fort Campbell, Kentucky and advanced training at Fort Knox, Kentucky finally traveling to Fort Benning, Georgia where he volunteered for the training known as “Jump School” , to become an elite Army paratrooper. On July 14, 1967 Private First Class Ward arrived in Vietnam and was assigned to the 5891st Military Assistance Command Vietnam commonly referred to as MACV. Little did the 20 year old PFC Ward realize that he was arriving in Vietnam just before one of the most pivotal moments of the entire war.

PFC Ward was assigned as the radio operator for the 45 Regimental Team 33, MACV. The MACV were divided into teams and most of the time operated alone and with the indigenous South Vietnamese Forces. The duty with the MACV teams was dangerous and Doug was tasked with a critically important job being the radio operator for the Senior Advisor to the 2nd Battalion 23rd Infantry Division ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam ). It was Doug’s job to call in airstrikes or artillery fire from U.S. forces when superior numbers of enemy were encountered. Doug’s job as a radio operator along with serving on a MACV team is evidence that he must have been level headed soldier under fire. His important task dictated that PFC Ward would be located at the front lines of battle, and such was the case on the day he fell in the service of his country.

In January of 1968 several events in Vietnam would make this period one of the most dangerous for soldiers serving in Vietnam. One of the events, the siege of Khe Sanh, would be a dark epic that forecasted future occurences. Khe Sanh was a U.S. Marine outpost that was located just south of the demilitarized zone and near the Laotian border. The strategic location of Khe Sanh made the base a natural target for the regular and irregular communist forces of North Vietnam. In the ladder part of 1967, Intelligence reports indicated that the North Vietnamese were gathering a large force near the base. The force included four infantry divisions, two artillery regiments and a ad hoc unit of tanks. The total estimate of men converging on Khe Sang was 40,000. This appeared to most U.S. military leaders and especially General Westmoreland, as a prime opportunity to demonstrate the superior American firepower and eliminate a major North Vietnamese force. On January 21st 1968 after a series of probing attacks the North Vietnamese attacked Khe Sanh in force. 5 The siege at Khe Sanh lasted seventy seven days and was the dominating news story in the United States and abroad. The American forces prevailed, but it was a hard fought victory. When the battle ended the North Vietnamese lost over 10,000 soldiers in the battle while the American Forces lost 500. The attack, however, was an elaborate ruse on the part The North Vietnamese General, Vo Nguyen Giap. General Giap was a competent military strategist and had orchestrated the attack on Khe Sanh to draw the American forces out of the population centers in the South for the upcoming Tet offensive.

The North Vietnamese General, Vo Nguyen Giap had been planning for a massive surprise attack of the south since September of 1967.11 The attack was earmarked to begin on January 31, 1968 and was the first day of the Lunar New Year. The Lunar New Year is the most important holiday on the Vietnamese calendar and had been informally honored as a day of truce in years past. In this respect, General Giap could be certain that the North Vietnamese soldiers and the Viet-Cong would have the element of surprise as an ally when the attacks begun. After the initial attacks of the Tet offensive as it is now known, the American General Westmoreland made a televised appearance stating: “The Communists had very deceitfully taken advantage of the Tet truce to create maximum consternation,” he concluded with: “their well laid plans went afoul.” 10

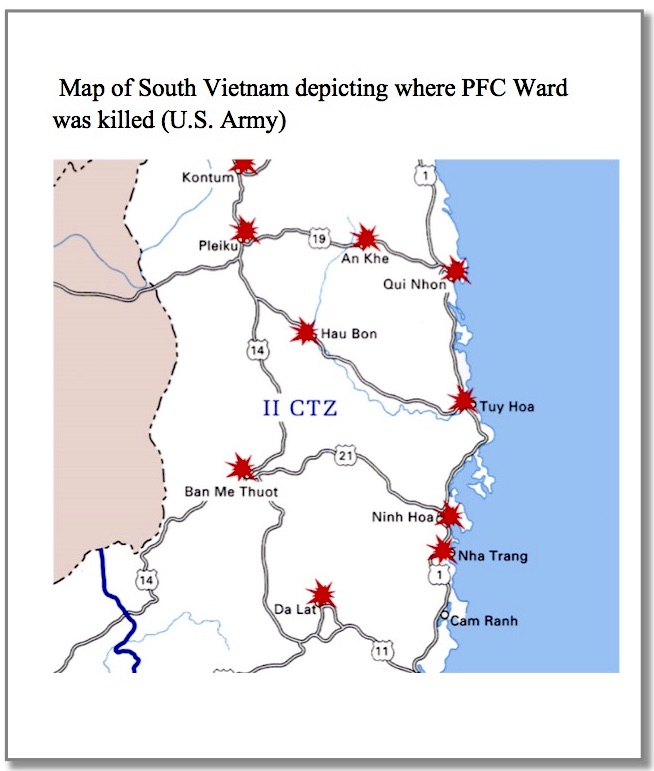

The town in Vietnam where PFC Ward was killed is known as Ban Me Thuot, which is situated in the Central Highlands Region of Vietnam. Ban Me Thuot is the capital of the Darlac Province and was home to 65,000 inhabitants in 1968.2,3 Ban Me Thuot was also the home base of the headquarters of the 45th Regiment MACV.6 The headquarters of the 45th Regiment along with the airfields and at least one bank were attacked by the 33d NVA (North Vietnamese Army) Regiment with support from the 301 E VC (Viet Cong) LF Battalion. The area was attacked a full day ahead of General Giap’s schedule. General Giap had intended all of the attacks of the Tet offensive to begin on January 31, 1968. The reason for the premature attack was actually a calendar problem. The large amount of cities that were attacked in the South required coordination and General Giap’s orders were to attack all the cities “on the first day of the Lunar new year.” There were two calendars in circulation in 1968, an old and newer version. In the fog of war a small detail was overlooked by General Giap which facilitated the early attack 4,3 The attack on Ban Me Thuot began after midnight on January 30, 1968 and consisted of over 2000 North Vietnamese soldiers and was accompanied by both rocket and mortar fire.4 At Ban Me Thuot the US and South Vietnamese forces had taken measures to prepare for the impending attack. The South Vietnamese Army had actually captured the plans of the NVA forces. Before the attack, South Vietnamese Commander, Colonel Dao Quang had sent patrols out to engage the enemy on the outskirts of the city.9 In short order, the NVA and the Viet-Cong were in the town and the fighting was so intense it was described as a “house to house affair”. On the day of his death PFC Ward would have been fighting the NVA and the Viet Cong since the pre dawn hours of January 30. Being the radio operator for the senior advisor, 2nd Battalion, 23rd Infantry Division ARVN, you can be certain PFC Ward would have been on the front lines of battle the entire time. The 45th regiment finally requested help and the US command called in the 1st battalion of the 503rd Airborne Infantry from the neighboring base at Pleiku, but even then it took till February 6th to eliminate the enemy forces within the region.7 When the fighting ceased over 33 percent of the town was in ruins.

On February 2, 1968 while the fighting at Ban Me Thuot continued, John Ward Sr. was visited in Lancing by a U.S. Army officer. He must have realized that this visit had ominous consequences. The officer carried with him a telegram from the Department of the Army and stated the following:

“Your son died in Vietnam on 31 January 1968 from gunshot wound received while marking air strike targets when hit by hostile automatic small arms fire.”

John Sr., in the company of the Army Officer and Lou Christmas, traveled to Rockwood to deliver the tragic news to Doug’s mother, Hazel, who was working at the hosiery mill. At this time the Ward family only received scant details of their son’s death. On February 23, 1968 after the U.S. forces in Vietnam had regained composure following the Tet offensive, the Ward family received the following letter regarding the death of their only son, Doug:

“On behalf of the officers and men of the 45th Regiment, I extend to you condolences and sincere sympathy on the loss of your son, John.”

John was instantly killed by automatic weapons fire shortly after 1 p.m. on 31 January 1968. As radio operator to the Senior Advisor of 2d Battalion, John was accompanying his battalion as they launched an offensive against a Viet Cong stronghold located within the city of Ban Me Thout.

When the attack stalled due to enemy automatic weapons, anti-tank, and mortar fire, a team of US advisors went forward to a position from which they could direct an air strike on the enemy. John was with this team. As the men arrived at the forward position the Viet Cong counter-attacked. One US officer was killed and another wounded. Although John was ordered to “pull back” he refused to leave the wounded officer unattended. John called for assistance using his radio, as two men were helping the wounded officer to the rear. John covered their move by firing at the enemy. It was during this exchange of fire that John was mortally wounded.

If it is any solace to you John gave up his life defending a wounded comrade, and in doing so has established a courageous example to all those who serve in uniform. We in the 45th Regiment share your grief for we had come to love and respect John as a man and a friend. We shall never Forget!”

–James R. Brooks

Major, Infantry

SA, 45th Regiment

23rd Infantry Division 8

In closing: John Douglas Ward Jr. along with 58,000 other American soldiers gave their life when their country issued the call during the Vietnam War. As citizens, we all own PFC Ward and the countless other Vietnam Veterans a debt of gratitude and respect for their service and sacrifice. PFC Ward is honored on panel 36E, line 041 of the Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington D.C. I would like to thank Hazel Ward and Lou Christmas and Margaret Larue for providing information that allowed this story to be written. I would also like to especially thank Ronnie Trout for his previous efforts in recognizing Doug’s service.

Bibliography

1. History.com Staff. (2009). Tet Offensive. Retrieved February 21, 2017, from http://www.history.com/topics/vietnam-war/tet-offensive

2. PAUL WEDEL | United Press International. “1968 Tet Offensive Marked Turning Point in U.S. Loss in Vietnam.” Los Angeles Times. January 31, 1988. Accessed February 21, 2017. http://articles.latimes.com/1988-01-31/news/mn-39430_1_tet-offensive.

3. Willbanks, James H. The Tet Offensive: a concise history. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007, 166

4. Willbanks, James H. The Tet Offensive: a concise history. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007, 29

5. Callahan, Shawn P. Close air support and the Battle for Khe Sanh. Quantico, VA: History Division, U.S. Marine Corps, 2009, 65

6. Clarke, Jeffrey J. Advice and support: the final years, 1965-1973. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1992, 397

7. Stanton, Shelby L. The Rise and Fall of an American Army: U.S. Ground Forces in Vietnam 1965-1973. Stevenage: SPA Books, 1989, 237-239

8. Morgan County News, February 1968

9. Anderson, Dale. The Tet Offensive: Turning Point of the Vietnam War. Minneapolis, MN: Compass Point Books, 2006,42-43

10. Willbanks, James H. The Tet Offensive: a concise history. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007, 56

11. Karnow, Stanley. Vietnam: 2a History. 7th ed. New York: Viking Press, 1983, 535

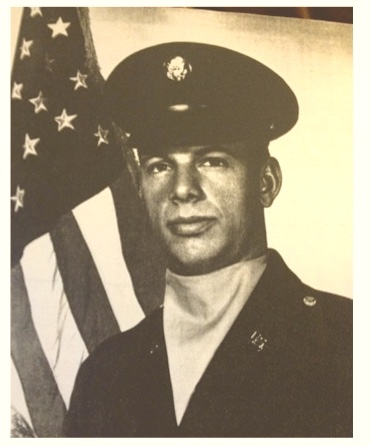

Note: The 1967 Photo of John D. Ward Jr. is by Lou Christmas

- Rank: Private First Class

- Date of birth: 16 August 1947

- Date of death: 31 January 1968

- County: Morgan

- Hometown: Lancing

- Service Branch: Army

- Division/Assignment: Advisory Team 33

- Conflict: Vietnam

- Battles: Tet Offensive

- Awards: Purple Heart

- Burial/Memorial Location: Mount Hope Cemetery, Morgan County, TN

- Location In Memorial: Pillar XXIV, Top Panel

- Contact us to sponsor John D. Ward Jr.

Image Gallery

Click a thumbnail below to view at full size.