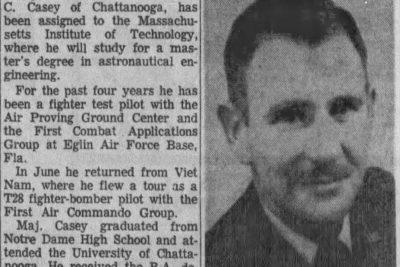

Donald Francis Casey served during World War II, Korea and Vietnam. He had done one tour in Vietnam, when he volunteered to go back.

He was the son of William Christopher Casey and Mildred H. Dempster. He was the husband of Katherine “Kitty” L. Lynskey and father of Stephen Bryan Casey and Maureen Casey

He was killed when his F-4 crashed while on a bombing run in North Vietnam Jun 23, 1968. He was listed MIA until he was declared dead Feb 6, 1979. His body was not recovered.

Story from 60 Minutes – Leave no one behind

Today, tens of thousands of American families hope and pray that their loved ones serving in Iraq and Afghanistan will return home safely. But imagine if 90,000 U.S. servicemen and women simply vanished. That’s how many Americans remain unaccounted for from WWII, Korea and Vietnam. Correspondent Vicki Mabrey caught up with one of those teams in Vietnam, as its members tried to fulfill the military’s pledge to its soldiers: that it will leave no one behind. Today, Vietnam is at peace, and the scars of war are buried beneath a fresh jungle canopy. Yet American soldiers return to this once enemy territory, not with guns and napalm, but with shovels and picks.

They are from the joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, or J-PAC, and they came in this case to search for the remains of two Air Force pilots whose plane crashed in the jungle more than 35 years ago. The team consisted of a dozen military specialists and one civilian. On the mission was 32-year-old Sabrina Taala, an anthropologist who led the excavation.

“We know a plane crashed here. Now we’re looking for items that would indicate that individuals were in the plane at the time it crashed,” said Taala. “Because if we can find evidence that shows that, then we can be sure that nobody punched out, survived and something else happened.” Like any archaeological dig, the work is painstaking, and requires scores of laborers. The team hired 120 Vietnamese villagers, who hike a couple of hours every morning to reach the site. First they cleared away the trees, then Taala laid out a grid the size of half a football field. “We pass it through quarter-inch mesh screen, and Americans and locals help them look for any items that might be relevant,” said Taala. “Anything that might be life support, anything that looks like it belongs to a plane and not the earth. Anything that they think might be bone. Although, if they found something like that, they would call me over. And then, they take anything that they find, and they throw it in a bucket, and then we analyze it when they’re done.”

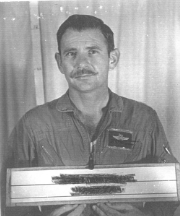

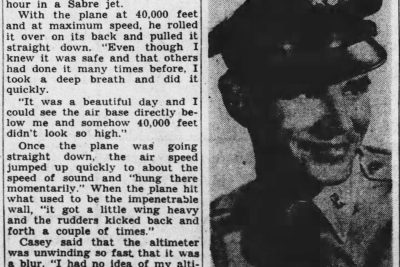

Taala’s team was searching for the remains of Lt. Col. Donald Casey and First Lt. James Booth, two Air Force pilots sent to Vietnam to bomb mountains 35 years ago. Casey, 42, was a career military man who’d already served during WWII, Korea, and had done one tour in Vietnam, when he volunteered to go back. Casey’s wife, Kitty, now 75, remembers the day 35 years ago when he left their home in Florida. “We were saying goodbye and he said, ‘Kitty.’ And I said, ‘Yes?’ And he said, ‘If anything happens to me, and my wingman comes home and tells you I’m dead, believe him,'” recalled Kitty Casey. “He said, ‘And start a life for yourself immediately.'” They were the words of a veteran flyer who’d seen so many young wives wait for husbands who were never coming back.

Casey’s mission was to bomb targets along the infamous Ho Chi Minh trail, an effort to stop Viet Cong troops and supplies from infiltrating the south. And so on the evening of June 23, 1968, he climbed aboard his F4D phantom fighter – shortly after recording a message to his wife and their three children. “He said, ‘There’s a USO tour here tonight. And all the young guys want to go see the girls.’ And he said, ‘So, since I’m the old man, I’m going to take this night flight,'” related Kitty. “And he said, ‘I miss all of you so much. I feel as if my heart will break.’ And he said, ‘I feel like it will be an eternity before I see you again.’ And with that, the tape clicked off.” Minutes later, Casey and Booth took off on their bombing run. They were never heard from again.

With the pilots lost deep in enemy territory, it was too dangerous to send in search and rescue teams. Donald Casey and James Booth were classified as “Missing in Action.” As promised days after the crash, the wingman called Kitty Casey. “One of the first things I said to him, I said, ‘Bob, is Donald alive?’ And he said no,” said Kitty, who said she still had hope. There was never a funeral. Even though he was a hero, did he receive the accolades that he deserved? “No one really cared,” said Kitty.

But the U.S. military never stopped caring about Donald Casey. So when relations with Vietnam began improving in the early ’90s, JPAC started trying to locate Casey’s crash site. In the Vietnamese archives, they found photographs taken in 1968 of what officials said was the wreckage of the plane. Then, in 1997, witnesses led a team to a ravine. This year, the digging finally began. On the day 60 Minutes II visited the site, evidence about Casey and Booth was sparse – there were just a few chunks of twisted metal. But Taala said that is part of the process: “We can’t come out here and find something great every day.” But a good day, she said, makes the bad days worthwhile. “You can go 29 days and find nothing but dirt, not even one tiny piece of metal. But if you get that one item that you can link to somebody, a personal effect, an ID tag, a watch, a ring, it makes it all worthwhile. It makes weeks and weeks and weeks of work worthwhile.” Everything that’s found is sent to the Joint Accounting Command’s laboratory at Hickam Air Force Base in Honolulu. Scientific Director Thomas Holland and his team analyze every fragment. Holland showed 60 Minutes II how they were trying to build a life from what was found at the site we visited in Vietnam. “We’ve got a variety of items here. This is part of an Air Force issue survival vest – evidence that someone was in that aircraft,” said Holland. “We’ve recovered a number of fragments of survival map. We’ve got fragments – these are boot eyelets.” Nothing, he said, is too small. In fact, one of the most important items so far is the back of a watch. “This is an item that would have been strapped to an individual. So when the issue then becomes did they get out of the aircraft? This is a pretty good indicator that at least one of the individuals did not make it out of the aircraft,” said Holland. It will take months to determine whether these items belonged to Casey or Booth. Meanwhile, what they’re hoping to find is a piece of bone or a tooth that can be identified through DNA or dental records.

I have a bracelet that my father gave to me when I was very young. Lt. Col. Donald Casey 6-23-68 on it

I am wondering if someone in their family would like this bracelet.

Jodi McClellan

(720) 273-6843

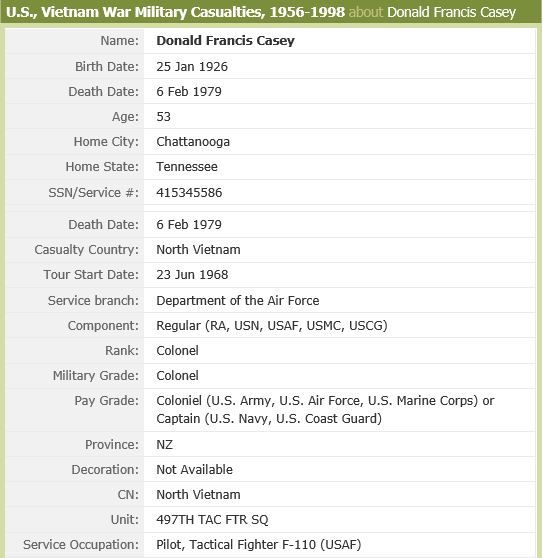

- Rank: Colonel

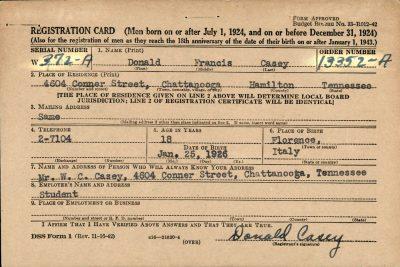

- Date of birth: 25 January 1926

- Date of death: 23 June 1968

- County: Hamilton

- Hometown: Chattanooga

- Service Branch: Air Force

- Division/Assignment: 497th Tactical Fighter Squadron

- Conflict: Vietnam

- Location In Memorial: Pillar XXIII, Top Panel

- Contact us to sponsor Donald F. Casey

Image Gallery

Click a thumbnail below to view at full size.