Abraham Lincoln Hill was the son of Spencer B. “Spence” Hill and Margaret Lula Mary Whitehead.

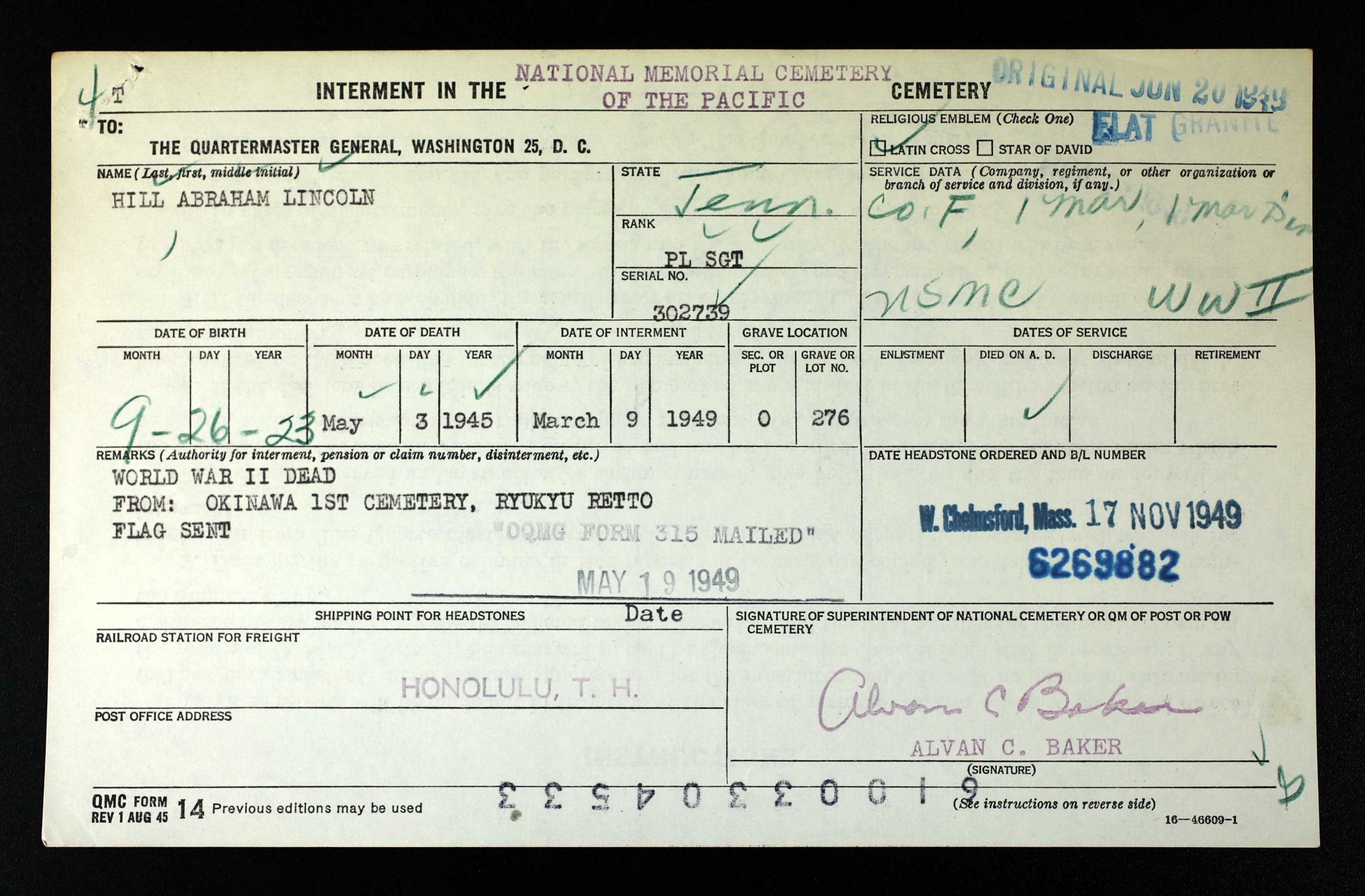

He was killed at Okinawa and initially buried at Okinawa 1st Cemetery, Ryukyu Retto.

The Knoxville Journal, 11 November 1949:

The story of Lincoln Hill as told herewith is a way the saga of many a youth who went from the hills and valleys of East Tennessee to give his life for his country on foreign soil. Lincoln Hill was not just one fine young man, he might have been any one of those who grew up in similar circumstances, and then died for his country.

This Armistice Day is the fifth since Lincoln was buried in grave 192 on Okinawa. Like most of the millions who have died in America’s wars, young Hill is remembered by few except in his own community and in the little cluster of fighting men who survived him. The story of his life is thus divided into two chapters – one that begins in the sweet, green foothills of the Smokies and one that ends on the bitter, blood-soaked heights of a remote Pacific island.

Little is known of his death except what has been written on Marine Corps records. It’s the story of his life, despite its peaceful setting, which still starts tears to flowing whenever his name is mentioned in Six Mile Community near Maryville.

The only child of what was a second marriage for both his mother and father, he was born in Happy Valley and christened Abraham Lincoln Hill. Both parents had large families by their first marriages. Lincoln’s mother died when he was two years old. A year later, Lincoln and his daddy moved from Happy Valley to Six Mile. The young boy’s half-brothers and sister from his mother’s first marriage went to live with their grandparents. They wanted to take Lincoln, but his father said no – he’d raise his own boy. That was the beginning of Lincoln’s loneliness. His daddy was strong willed and not much given to affection. There were a number of housekeepers who came to the big cabin in the hollow through the years, but they were all strangers as the boy grew in shyness. His daddy was a saving person – didn’t believe in burning an oil lamp after dark, thought the light from pine knots burning in the open fireplace was enough. So, on most nights, Lincoln sat by the fire in silence while his daddy picked a five-string banjo or sawed an old fiddle. Lincoln must have felt, when he left Six Mile to join the Marines in December of 1941, that his only true friend was an old hound-dog named Chuck. There were tears in his eyes when he left Chuck. Lincoln was 17 then.

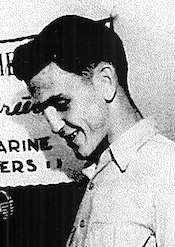

Lincoln liked the Marines from the first, and as he gradually lost his shyness, the Marines liked him. One of the friends he made in those early months at the New River, N.C., training camp was a boy from Brooklyn who later was to write the letter telling how Lincoln had died. When Lincoln got his first furlough he climbed off the “Blue Goose,” the bus that ran from Maryville to Six-Mile, his old neighbors didn’t recognize him as he started up the hollow. His eyes and teeth flashed, the same perpetual smile, but it was his bearing that was different. His six-foot height somehow seemed like a lot more the way he carried it, and his uniform emphasized the extra weight and muscle he’d put on. He never lacked an audience when he told, in a language that also seemed different, of the places he’d been and the things he’d seen. Before the young soldier went back to camp, he took a last look at the mark he’d made on his Aunt Maudia’s pantry ceiling just before he enlisted. That was after she had told him, “You’re a good boy. You’ll make your mark someday.”

“I think I’ll make it now,” he had answered, “Leave it there until I come back.” The penciled cross-mark is still there eight years later. Young Hill went overseas early in 1944, as a Sergeant with the 92nd Battalion of the First Marine Division. He was wounded later that year at Pelilieu, but recovered rapidly.

His letter home, to his father and half-brothers and sisters on both sides, were completely lacking in details of his experiences. They were mostly the cheerful kind – how good the chow was and how he must have been born under a lucky star. “I just came through one of the biggest battles the Marine Corps has ever fought, and I’m still alive, ain’t I?” Lincoln had risen to platoon sergeant when his outfit went in on Okinawa. The friend from Brooklyn wrote to tell that he had died on May 3, 1945. A Jap bullet struck him in the left temple as Lincoln crawled out of a ravine to pull in a wounded Leatherneck. “He was the cleanest guy in the outfit. It just didn’t seem like it was his time to go,” the friend from Brooklyn wrote. Lincoln’s body, along with those of his comrades who died on Okinawa, has since been removed to the big military cemetery in Hawaii. Until his daddy died earlier this year, Lincoln’s picture hung by the fireplace in the big cabin in the hollow, where the blaze from the pine knots would flicker across his smiling face and bring tears to the old man’s eyes – tears that had never been seen while Lincoln was alive.

- Rank: Platoon Sergeant

- Date of birth: 26 September 1923

- Date of death: 3 May 1945

- County: Blount

- Hometown: Maryville

- Service Branch: Marine Corps

- Division/Assignment: 1st Marines, 1st Marine Division

- Theater: Pacific

- Conflict: World War II

- Battles: Okinawa

- Awards: Purple Heart, Gold Star

- Burial/Memorial Location: Honolulu Memorial, Honolulu, Hawaii

- Location In Memorial: Pillar VI, Middle Panel

- Sponsored by: Georgann Hill Hickman

Image Gallery

Click a thumbnail below to view at full size.