In the valley of Second Creek, just west of the busy commercial district of Knoxville, they stand silent and vigilant. Stone sentinels in platoon strength parade on an acre of grass amidst an industrious, noisy city. Arrayed in two squads in military precision, the ranks of granite stones, each twelve feet high, a foot deep and four feet across the face, stand watch over the names of those who stood watch over us.

The site of the Knoxville World’s Fair of 1982 was quickly converted to multiple public uses after the close of the last profitable such exposition. The fair comprised an area that ran north to south and was confined mostly between the west shoulder of the Knoxville business district and Second Creek which flows south into the Tennessee River a scant quarter mile away.

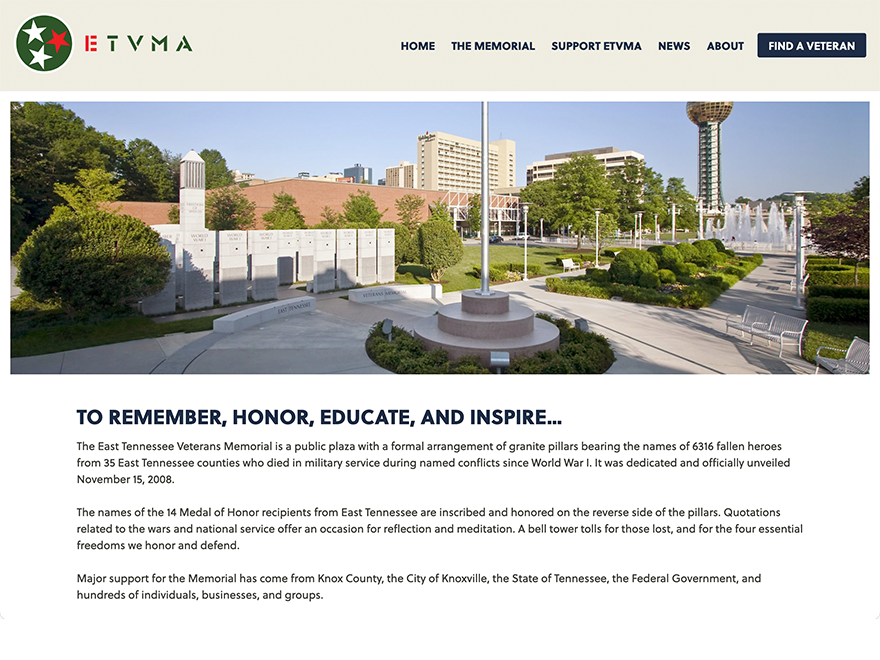

The northern half of the fair area is covered with a swath of green grass interrupted only by a fountain pool and surrounded by shade trees. The far northern end of the plain is the site of the East Tennessee Veterans Memorial. It stands quiet and serene in contrast to the ever-changing activity that swirls around it.

Immediately to the north of the memorial stands the ponderous L&N Railway Station, built in 1905 and now home to the L&N STEM Academy. The station enjoys some small notoriety for being included in several scenes in James Agee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, A Death in the Family. The imposing red brick Victorian style structure hovers over the site and dominates the northern horizon and carries the badge of inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places.

To the west of the memorial stands the old L&N freight house. Like the station, it is constructed of red brick and has been converted to more modern uses including offices and classrooms. The multiple tracks that once led into the terminal and freight house have, like the steam locomotives they once served, long since departed. No evidence of them remains in the open field of grass. It now serves running children, frisbees and the occasional festival.

Behind the freight house and running along the banks of Second Creek lies a single-track railroad that links the Norfolk Southern main line to the Gulf & Ohio Railway which serves local industries on both sides of the Tennessee River. An occasional switch engine sporting the red wings of the Gulf & Ohio logo will pass, the engineer entertaining the playing children with multiple blasts from the chimes, or air horn. Children run to see the engine and wave, then run back to the fountain pool to laugh and jump about very much like fish out of water.

The fountain pool is bordered by a play area filled with swings and all manner of devices meant to entertain kids and make them ready for sleep. The children run from the fountain pool to the play area and back again while their parents sit on benches or blankets on the ground wondering what it was like to have that same energy so long ago. Water shoots into the air from the jets in the fountain pool in syncopated rhythms to which the children dance and squeal. Parents chat while runners make their rounds and college students throw footballs in the wide field.

Further to the southwest and across Second Creek stands the Knoxville Museum of Art, its pink Tennessee marble facade and oversize windows monitoring the passing people in the World’s Fair Park, the occasional train and the ever-present activities.

Around the whole run the busy streets of a medium-sized city, humming with truck and bus traffic, blaring horns and the constant vibrations of commercial life. There is no quiet place, no refuge from the sounds or the dominating buildings, such as the Tennessean Hotel which towers over the southeastern corner of the grounds; except for the memorial.

With all the commotion, noise and vibrant activity of the surroundings, the memorial stands as a place of peace, perfectly still, immoveable, almost tranquil. Life flows around it as though the memorial were a large stone set in the middle of a swiftly moving mountain stream. It is a constant reminder of how and why our children play and laugh while we lounge on the grass and smile at their antics. We live our lives with the potential for goodness and peace and happiness, in part, through the existence of such pools of consideration. This memorial, like countless others just like it across the country, remind us of our great fortune to have men and women who are always vigilant, always prepared, always watching.

Arrayed like a camp picket around three sides of the perimeter of the memorial are holly trees and bushes, arranged in perfect military order and trimmed to reveal a glimpse of the sentries standing guard inside, yet not the whole. On the most recent day I visited, one tree was brightened with a red, white, and blue bow secured at eye level. Someone who remembered was grateful and had paused to consider and leave their own small memorial.

The entrance to the west side of the plot presents a full view of the ranks of stones which bear the circle and three stars of the Tennessee state flag representing the three geographical areas of the state.

The great granite stones serve to remind the visitor of those who stand between us and those whose greatest wish is to do us harm. They also stand in stark testimony to the cost of that vigilance. The names of more than six thousand seven hundred lives are inscribed upon the polished western face of each four-foot-wide stone. While they stand and serve to remind us of our good fortune, their true service is far greater. The great stone columns stand to memorialize and protect the names of those who saw something greater than self, something worth giving their all to preserve and pass on to others. The stones stand guard over the names and their memories.

The columns are assembled in ranks, four abreast, divided into two squads separated by a central pathway. Atop each column is a designation of the conflict from which the names are drawn beginning with the First World War and continuing through our current military conflicts. The individual names are grouped by county of origin. The stone columns are a light grey in color but burn a bright white in the direct sunlight as the crystals reflect the sun. Running fingers over their surface reveals a familiar, slightly granular texture that recalls ballast stones used in railroad rights of way. Even on the warmest days, they are cool to the touch. Only the facings of the stones that bear the many inscribed names are polished smooth. Visitors run fingers along the many lines of names, searching for a family member or friend. Some pull out paper and pencil to make a charcoal impression of a sought-after name.

The central walkway and the viewing paths between the ranks are, like the standing stones themselves, of granite, which hardens with age. The grass at the foot of each rank, front and rear, is manicured to consistency and accompanied by granite benches on which visitors sit on occasion and consider the cost. A stone bench at the entrance is inscribed with the command to “Please act with propriety in order that these men and women be properly honored”.

Propriety is the order of the day as people wander into the quiet space, just yards from shrieking children engrossed in play. There is about the place a reverential quiet, even amongst so much noise. It is as though the holly trees and bushes serve not just to partially obstruct vision, but to serve as a sound barrier as well. They work together to insulate the nave of the memorial from the laughing and celebrating families. Those who alter course tend enter do so with a quiet reflection, slowing their step as though they sense they’ve wandered into a sacred space. At times, the breeze carries the scent of sun block from those headed to the fountains.

An occasional national flag is pressed into the soil before a few of the stones, left by family members who wait and consider. Boisterous young men cease their laughing and cast sideways glances as they pass the entrance, hesitant to enter but curious. Young families with children in tow wander through and read the names on the stone facings and wonder who was Tom B. Chrisman of Jefferson County, Tennessee and the six thousand others.

Tom Chrisman was a Marine who volunteered in the highest tradition of his native state to serve in a time of great conflict. He had just married his young wife when he was deployed to the Pacific and waded into the hell that was Peleliu Island in September of 1944. His young wife never remarried and passed into eternity with Tom seventy-two years later. All that remains is his name, etched into the smooth granite face of a stone column that protects it for anyone who wishes to see, remember and honor in the quiet and solitude of their thoughts.

Other names are more recognizable. The rear, or eastern face, of fourteen columns is devoted to the men from East Tennessee who were awarded the Medal of Honor. The Medal of Honor is never “won”. It’s not some prize that might be sought after to increase one’s esteem among others or never again need to pay for a beer. It is a memorial all its own to the valor and selfless sacrifice of those who saw something greater than themselves and elected to fight to preserve it in the ultimate fashion. Most do not survive their commitment to their beliefs to return home. The names, alone given a place of high honor, ring out. Their unit and rank as well as the site of their acts of courage are inscribed, but the specifics of their sacrifices are absent. It is in the charge of the reader to search and find the stories behind the names. Truly honoring those who serve us requires that we investigate, that we strive to learn and to know and in the knowing, we can remember. We remember men like Troy McGill and Paul Huff. We strive to understand men like Alexander Bonnyman while we recognize the name of Alvin York. They are all there, the names preserved and protected by the tall columns.

The names lend emphasis to something greater still, and that is the consciousness of a nation to its founding principles and its heritage. One column speaks to this reality with a quote from President John Kennedy. The viewer must tilt the head back to see high up on the column the words, “A nation reveals itself not only by the men it produces but also by the men it honors, the men it remembers”. Individuals stand and read the words. I watch them and wonder if they grasp their significance, if they understand the weight of President Kennedy’s convictions and their application to today and how we honor, or not, the men who made possible the greatness of our towns, our cities and our national character.

Two things, though, stand above the names, above the remembrance of their sacrifices. At the rear of the memorial rises a bell tower. Standing at twenty-four feet, it dominates the memorial from the east. Behind the bell tower sitting low to the ground rest five shallow, round planters filled to overflowing with yellow lantana. The bright colors are a stark contrast to the grey stone that dominates the area.

Inscribed high on the four sides of the bell tower are the four essential freedoms spoken of by President Roosevelt; the freedom of speech, the freedom from fear, the freedom from want, and the freedom of worship. The list of essential freedoms, as he referred to it, tells us more about Mr. Franklin Roosevelt than it does about the ideals of our country, I think. Still, the ideal of freedom rises even above the names of those who gave all they had to preserve it.

At the opposite end of the memorial, mounted in a circle of granite steps facing the entrance and the bell tower, stands a flag staff. The national flag is always flying, illuminated at night, like the stones, with bright light. The bell tower of freedom is possible because of the flag flying from the staff. They are both made possible by the names on the stone columns who are remembered and memorialized by the acre of land set amidst the hustle of a city that seldom notices.

The artist who designed the memorial identified our obligation to the names inscribed on the stones. Near the words of President Kennedy is found a poem written on New Year’s Day of 1970 by Major Michael Davis O’Donnell.

If you are able, save for them a place inside of you and save one backward glance when you are leaving for the places they can no longer go. Be not ashamed to say you loved them, though you may or may not have always. Take what they have left and what they have taught you with their dying and keep it with your own. And in that time when men decide and feel safe to call the war insane, take one moment to embrace those gentle heroes you left behind.

Three months after writing these words, Major O’Donnell, a helicopter pilot, was reported missing over Cambodia. His remains were eventually recovered and interred in Arlington National Cemetery on 16 August 2001.

The memorial stands and waits. It awaits the next visitor, the next Veteran’s Day service, the next tide of children running to the fountain pool and the next conflict. Room remains on the stones for more names, more servants, more stories. Wars are fought, names are added, and families remember.

The East Tennessee Veterans Memorial stands silent and eternal that we might save one backward glance and remember and embrace those who no longer can walk with us.

(with thanks to author Michael Sawyer for allowing us to publish)